When the Sun Breaks Through

Jan 13, 2025

Chapter 1 - Stolen Hope

David-Baya crouched near the edge of their makeshift shelter; his knees pressed into the damp dirt floor. He saw his father, Jean-Kiba, sitting just outside through a small hole in the patched plastic wall. The dawn light painted the sky a soft gray, and the morning mist clung to the air. Jean-Kiba sat hunched forward, his face buried in his hands. His shoulders shook slightly.

David blinked in disbelief. His father was weeping. In all his twelve years, David had never seen him cry. Not even two years ago, when their village in the Kasai region of DR Congo was burning and chaos engulfed everything they had ever known. Jean-Kiba had been strong then, carrying David's little brother on his back and urging his family to run faster. But now, in the fragile quiet of the Nakival Refugee Settlement where they had found safety, he seemed to have crumbled.

The boy’s breath caught in his chest. Something must be wrong. He looked around the dim interior of the shelter. His mother, Amina-Mbali, was still sleeping, her arm protective over two-year-old Malaika. Nine-year-old Safi and six-year-old Kato, his other siblings, were curled under a worn blanket, their small forms rising and falling steadily. David’s gaze fell on the corner where their one chicken usually pecked at the dirt, even when they were sleeping. The bird was gone.

He put the pieces together slowly. The chicken—the last bit of livestock they had managed to keep through their harrowing escape and the months of hardship in the camp—was their only reliable food source. Its eggs were a small but vital addition to their sparse meals. If it were gone, stolen perhaps, the loss would weigh heavily on the whole family.

David-Baya hesitated, his small hand brushing against the tattered hem of his shirt. As he shifted to get up, a rusty nail sticking out of a wooden beam caught the fabric. There was a sharp tear. He froze, staring at the fresh rip in his only good shirt.

Jean-Kiba heard the sound and turned, his face streaked with tears. For a moment, they locked eyes, the father and son connected by an unspoken understanding. Jean-Kiba gestured for his eldest child to come closer. Instead of the reprimand David expected—for tearing the shirt or being awake so early—Jean-Kiba’s voice was soft and weary.

“Come sit with me, David,” he said.

David stepped cautiously outside, the cool morning air raising goosebumps on his arms. He lowered himself beside his father, staring out at the sparse landscape of the Kabazana village in the Nakivale Refugee Settlement. The morning sounds of the camp were beginning to stir: the cough of a neighbor, the low murmur of voices, the clatter of pots being arranged for breakfast. But here, at this moment, it felt as if the world had paused.

Jean-Kiba wiped his face with the back of his hand and placed a comforting arm around David’s shoulders. “I have failed you,” he said simply.

David’s chest tightened. “Papa, no...”

“It’s alright, mwâna wânga,” Jean-Kiba interrupted gently. “I have already forgiven myself.” Then he added, “You are twelve and old enough to understand some things now, and I want you to know why I was crying just now.”

David shook his head, unsure whether to speak. Jean-Kiba’s hand tightened slightly on his shoulder.

“Our chicken,” his father said, nodding toward the empty corner of their shelter. “It’s gone. Taken. Perhaps by a neighbor. Maybe by hunger itself. To me, it was once more than just a chicken. It was hope. One precious creature helping us to survive. A tiny piece of control over our own lives.” He exhaled deeply, his voice trembling. “And now it is gone.”

David-Baya stared at his father, unsure how to respond. The chicken was important to him, but not as important as seeing his father like this. “We still have each other,” the boy said timidly, his young voice trying to find strength.

Jean-Kiba turned to look at him, his eyes red but filled with something new. Was it gratitude? Understanding? David couldn’t quite tell.

“You’re right, David,” Jean-Kiba said after a long pause. “We do still have each other. And this morning... I’m beginning to see things differently.”

David’s brow furrowed in confusion. Jean-Kiba didn’t elaborate immediately. Instead, he pulled his son closer and stared out at the horizon. The sun was beginning to rise, casting a soft golden hue over the camp.

“Let me tell you about what I have come to understand,” Jean-Kiba said quietly, his voice steady. “About what I have learned over the past few months.”

And so, as the camp around them came to life, father and son sat together, the weight of their struggles mingling with the faintest glimmers of hope.

Chapter 2 - Buried Strength

Jean-Kiba sighed, his voice growing quieter as if the memory he was about to share was too heavy to hold. “David, do you remember before we came to Nakivale, I was a teacher at École Primaire de Lukanza in Congo, and your mother’s market stall was doing well? That was a time when I felt strong. I thought that we could face anything. But life has a way of testing even the strongest of us. I need to tell you about the man I used to be so you can understand the man I am now.”

David-Baya nodded solemnly, his young eyes fixed on his father’s face.

“When the rebels came to our village, they did not just burn our homes and take our animals. They took our peace, our dignity, and our hope … or so it seemed to me then. I remember the night so clearly. Your mother was packing what little we could carry, and I was outside with my friend Mulumba. He was a good man, funny and kind. He refused to leave his house. He thought he could reason with them.”

Jean-Kiba’s voice caught, and he looked away for a moment. “I watched as they killed him, David. They didn’t listen to his pleas. They didn’t see him as a human being. To them, he was just an obstacle. Everything in me wanted to help him and fight back, but I had to think of you, your mother, and your siblings. So I ran. I ran with Kato on my back. Mailaka was in your mother’s arms, and you and Safi were beside her. Every step we took felt like I was leaving my strength and everything good behind me.”

David’s small hand rested on his father’s knee. “Papa... it wasn’t your fault.”

Jean-Kiba nodded, but his expression remained heavy. “I know that now, mwâna wânga. But at the time, I didn’t. The guilt stayed with me. Even when we crossed the border and arrived here, I carried that guilt like a stone in my chest. And then... the losses continued. Our fields, our cows, your uncle Bahati who set out with us but never made it to Nakivale... all gone. Every day I woke up and thought, ‘What kind of man am I if I can’t protect my family?’”

He paused, his fingers tracing patterns in the dirt. “When we first arrived here, I tried to hold on to hope. I told myself I would find work, that we would rebuild. But there was no work at Nakivale, no way to provide. All I could do was watch as the rain came through the holes in our shelter, as your mother struggled to find enough food, and you and your siblings went hungry. I felt... useless.”

Jean-Kiba’s voice grew heavier. “I told myself I was better than the other refugees I had seen stumble out of the Kazungu Bar. But one day, I wanted to make my dark thoughts disappear, and I found myself there. Juma makes his alcohol from sugarcane. It’s cheap, and it dulls the pain. At first, I thought it was helping me forget, helping me escape the memories. But it didn’t take long before the drink became another weight I carried. I was angry and ashamed, and I took it out on your mother, on all of you. The man I used to be—the teacher, the provider, the protector—he was gone. And I didn’t know how to bring him back.”

David-Baya’s voice was barely above a whisper. “But you’re still here, Papa.”

Jean-Kiba smiled faintly, his hand resting on David’s shoulder. “Yes, I am. And I’m trying to find my way back to that man, for myself, for all of you. That’s why I cried this morning, David. Not just for the chicken but because I realized something. The strength I thought I lost... it was never truly gone. It was simply buried under all the pain, fear, and frustration. But it’s still there. And what I’m learning is how to find it again.”

He looked into his son’s eyes, his voice steady now. “We all experience hardship, mwâna wânga. But the strength to carry heavy burdens and still be happy is always within us. I want you to remember that.”

David nodded, his heart swelling with love for his father. Together, they sat silently as the sun rose higher, bathing the camp in light.

Chapter 3 - 3P Wisdom

Jean-Kiba shifted slightly, his voice growing softer but warmer. “David, there is something I want to share with you. Something I have learned from some people who have helped me in the last few months. It’s about what is inside all of us.”

David tilted his head, curious. “What do you mean, Papa?”

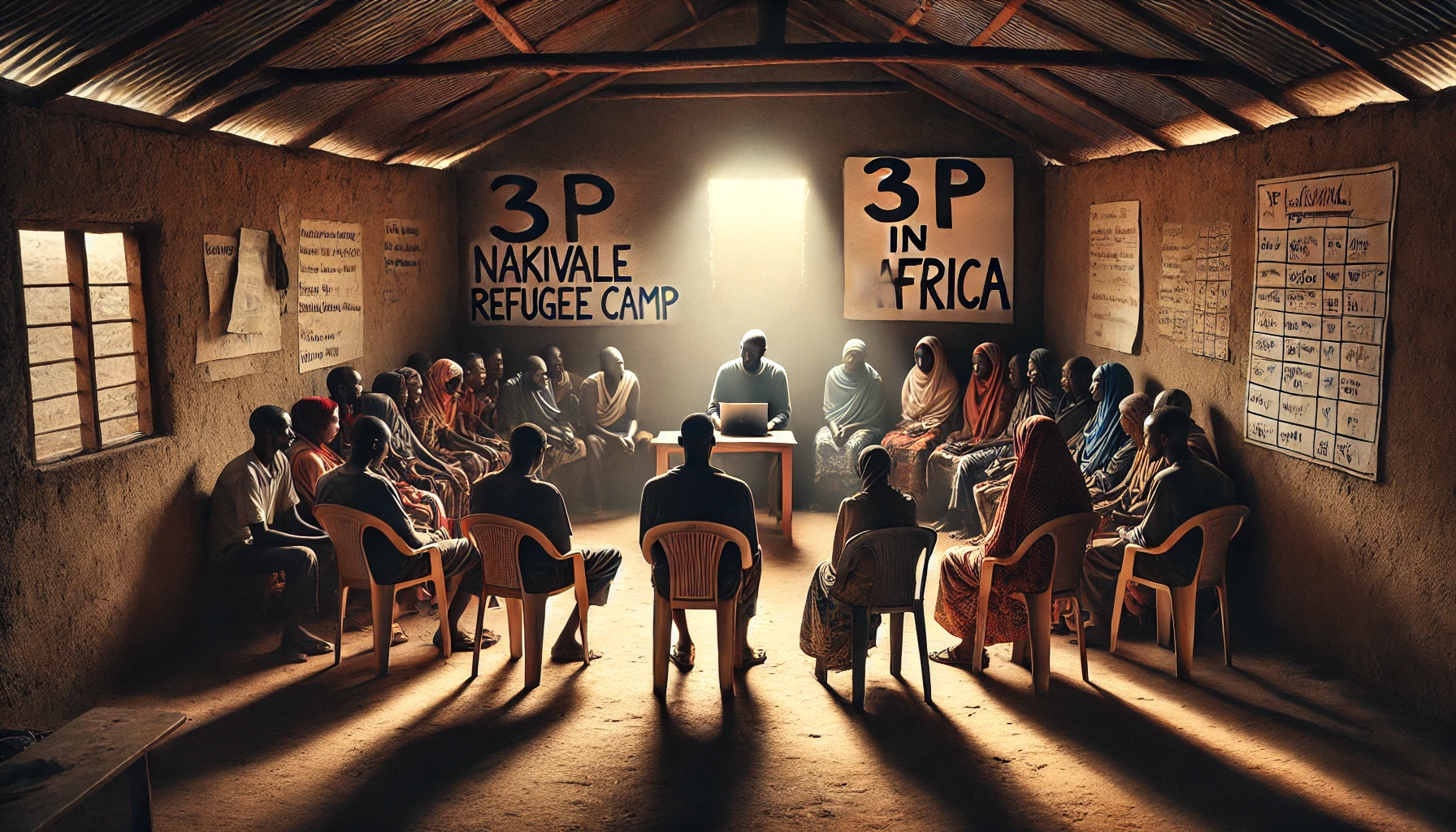

Jean-Kiba smiled gently. “Have you noticed that I’ve been gone on Thursdays in the afternoon and that your mother has been teaching you your lessons alone? I’ve been going to meetings here in Kabazana village. There’s a group of men, they call themselves the 3P Nakivale Alcohol Dept. They were once refugees, just like us. They even used to go to bars to drink, just like I did, but not anymore. Now, they go to villages in Nakivale to share something that changed their lives—and mine too.”

“What did they share?” David-Baya asked.

“They shared something called the 3 Principles, David. It’s about understanding all the spiritual gifts we were born with and how our mind works. Let me explain it this way. Do you remember when we discovered our chicken was gone this morning?”

David nodded. “Yes, Papa.”

“What did you feel when you first realized it was gone?” Jean-Kiba asked.

David thought for a moment. “I felt sad. And worried. I thought about how we wouldn’t have any eggs anymore.”

Jean-Kiba nodded. “Exactly. And that sadness and worry came from your thoughts. You see, David, we all have thoughts running through our minds all the time. When those thoughts weigh us down, like thinking about what we lost back home in the Congo or what might happen tomorrow when there are no eggs to eat, they make us feel heavy, too. That’s what these wise men call ‘overthinking.’”

David’s brow furrowed. “So... it’s my thoughts that made me feel bad?”

“Yes, mwâna wânga,” Jean-Kiba said. “But here is the beautiful thing. Just like clouds in the sky, those thoughts pass. If we let them go and don’t hold on to them, our minds become clear again. And when our minds are clear, we can see the sun. That sun is always there, David. It is our wisdom, our strength, our happiness. No one can take it from us. It is always inside us.”

David blinked, trying to understand. “So... when I feel bad, it’s because of my thoughts. And if I let them go, I can feel better again?”

Jean-Kiba smiled, pride shining in his eyes. “Exactly. And here is something else I’ve learned. I didn’t know I was making myself feel bad by holding on to my negative thoughts. But I know better now, and I’ve learned to forgive myself for not understanding this before and for taking out my fears and frustrations on your mother and you children. When we forgive ourselves and others, we open our hearts again. That’s how we heal. And when we heal, we find the strength and love that’s always been inside us, waiting to guide us.”

David was quiet for a moment, then asked, “Is that why you’ve been happier lately, Papa?”

Jean-Kiba’s smile widened. “Yes, David. Every time I listen to the 3P teachers and let go of my heavy thoughts, I feel lighter. I remember that I am strong. I remember that I can always find a solution no matter what happens. I can trust in my inner wisdom. A next step will occur to me in due time.”

Chapter 4 - Feeling Everything

David tilted his head a little skeptically. “But Papa, what if you feel... annoyed? Like when someone takes your only chicken. Is it okay to feel annoyed?”

Jean-Kiba nodded, his expression warm and understanding. “Yes, mwâna wânga, it is okay. It’s okay to feel annoyed, sad, angry, or worried. We are human beings, after all, and it is part of our nature to feel whatever we think. We cannot control what comes to our minds. When I found out that the chicken was gone this morning, I felt very annoyed!”

David’s eyes widened slightly. “You did?”

“Yes,” Jean-Kiba said. “I thought irritating thoughts about our neighbor Kabuya, who I had seen stalking around our shelter recently. It may have been him; it probably was. And for a moment, I felt very annoyed that someone had likely stolen our only chicken. But then I just let myself feel the annoyance and let it go.”

“Let it go?” David repeated.

Jean-Kiba nodded. “Yes, and as soon as I let it go, I felt something else. Compassion. I remembered that Kabuya was in a worse situation than us. He has eight children and no shelter at all. Maybe he took the chicken because his family is starving.”

David was quiet, absorbing his father’s words.

“As soon as I let the feeling of annoyance go, I started thinking clearly again,” Jean-Kiba continued. “I thought about speaking with your mother when she wakes up. You know how smart she is. She speaks Swahili, French, and Kikongo, and maybe she can arrange a trade—some of the vegetables we grow or the soap she makes—for another chicken. And if that doesn’t work out, I trust God will provide for us, as He always has.”

Jean-Kiba placed a hand gently on David’s shoulder. “So you see, my son, feeling annoyed, sad, worried, or scarred is okay. What matters is that we don’t hold on to those feelings too tightly. When we let them pass, like clouds in the sky, we can find our way back to clarity, love, and wisdom.”

David nodded slowly, his face thoughtful. “I think I understand, Papa. Letting the feelings go makes space for something better.”

Jean-Kiba smiled. “That’s exactly it, mwâna wânga.”

“My tears this morning were about that ‘something better,’” he said softly. “Because I’m grateful—so very grateful for this new understanding that has changed how I see things.”

David-Baya nodded slowly, the light of this understanding beginning to dawn in his young eyes. The sun broke through, and together, they sat in the growing warmth of the day, the beauty of hope and resilience shining quietly between them.

The End

I wrote these four chapters with the creative assistance of ChatGPT, a tool that helped bring my ideas to life. Together, we shaped this story to share the light of hope and resilience. Thank you for reading. Much love, Shailia Stephens (3P-in-Africa.org).

P.S.

This story was born from a heartfelt question I was asked while teaching the "3 Principles" in Kabazana Villiage in the Nakivale Refugee Camp. A man shared that his only chicken, a vital food source for his family, had been stolen. He asked, “Is it okay for me to feel annoyed, even though I understand the '3Ps' and know that forgiveness is the way?”

His question struck a chord deep within me. It captured the universal human experience of wrestling with emotions, even in the face of understanding and wisdom. That conversation inspired me to write this story, weaving together resilience, reflection, and hope into the lives of Jean-Kiba, David-Baya, and their family.

It’s a reminder that Thought creates feelings, and that our feelings are part of being human—and that in embracing them, we can find our way back to clarity, love, and wisdom.

Stay Connected With

News And Updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

You can connect to a general email list sign up form or turn this block off. When you update it, this will show (or not show) on every blog post at the bottom.

Wanna Get The

Awesome Freebie?

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Cras sed sapien quam. Sed dapibus est id enim facilisis, at posuere turpis adipiscing. Quisque sit amet dui dui.